When we think nostalgically about Christmas, as many of us do, we conjure up images of elegant Victorian houses with lavishly decorated Christmas trees reaching up to a high ceiling, holly draped over mirrors and mistletoe over doors, carol singing around the piano and happy children in their best party clothes. Apart from the Christmas tree clearly having originated from Germany and possibly first lit by candles in the early 16th century by Martin Luther, a lot of our glittery images of Christmas can be traced back to Victorian times in Britain, as described by Charles Dickens in several of his stories, and most especially in “A Christmas Carol”.

Portrait of Charles Dickens in 1842, by the American artist Francis Alexander. This oil painting is currently (2010) housed in Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts.

Born into a relatively affluent family in Portsmouth in 1812, Charles Dickens experienced both a comfortable life style during his childhood and a most uncomfortable one after his father was punished for living beyond his means by being thrown into a debtors’ jail called Marshalsea (as in “Little Dorrit”). Charles was sent to work at a rat-infested ‘blacking’ warehouse, where he had to work long hours putting tops onto pots of black boot polish under appalling conditions. What he witnessed there, as well as on the streets of London, and when he visited the Cornish tin mines made a great impression on him and deeply influenced his writing in later years. The many vivid, and often nasty characters who appear in his stories are largely based on people he encountered during this period of his life. His experiences in England, and also in the USA during his first visit in 1842, made him determined to expose the shocking gulf between wealth and poverty and to fight, not only for an improvement in living and working standards of the poor, but also for the abolition of slavery in America.

Going back to our image of an idyllic Christmas in Britain in Charles Dickens’ time, the mid 1800s, this is definitely that of the rich. Actually, in the early 1840s, the celebration of Christmas, (which was a combination of the Christian celebration of the birth of Christ, together with remnants of the Roman festival Saturnalia and a Druid ceremony marking the winter solstice) was waning in popularity. This was partly on account of Oliver Cromwell’s puritanical disapproval of the merrymaking of Christmas, and the fact that the poor had neither time nor money for it anyway! Being concerned, as he was, about the plight of the poor, Dickens must have been especially moved by the hardship of the disadvantaged at Christmas, supposedly a time to celebrate and make merry!

In 1843 Dickens wrote the first of his Christmas stories, “A Christmas Carol”. There can hardly be anyone who needs reminding of the story of Scrooge, as it is the most performed as play, musical, opera, ballet or pantomime, and the most filmed of any of Dickens’ works – IMDb.com quotes more than 25 major feature or TV films of this name, ranging from the 1910 version, to Robert Zemeckis’ latest 2009 IMAX 3D experience, animated film, with an all-star voice cast, including Jim Carrey, Gary Oldman and Colin Firth. Click on the amazon widget on the right to hear the soundtrack of the latter. IMDb.com also quotes many, many other variations on the title, including Flintstones, Barbie, Sesame Street, and Muppet Christmas Carol! If we were to include all of the amateur productions of this story (amateur dramatics groups/schools/clubs, etc., etc.) together with the countless professional ones, the numbers would run into thousands! There is a rendering of Dickens’ story to suit everybody. Reports on Zemeckis’ latest spectacle, using a highly advanced form of performance capture animation, range from how utterly amazing the visual effects are, to how very dark and sinister it is (well justifying its PG rating in Britain – scary for young ones) but all agree that it is pretty impressive!

Briefly, Ebenezer Scrooge, despite all his money, was a miserable, unhappy man and a hard, cruel boss to his clerk Bob Cratchet, who was a kind, lovable man, despite his circumstances. Scrooge begrudged him even one day free per year to celebrate Christmas, and made him work long hours in a freezing-cold office, paying him a pitence, on which medical help for his sick son, Tiny Tim, was out of the question. As the story unfolds, Scrooge is visited first by the ghost of his late partner, Jacob Marley, warning him to change his miserly ways before it is too late, and later by a succession of three spirits. The first one, “The spirit of Christmas past” shows him how lucky he was as a child; then “The spirit of Christmas present” shows him what a miserable soul he has become and the circumstances of others, and “The spirit of Christmas yet to come” shows him the dire consequences unless he does something about it. Between them, they succeed in changing his heart and mind, such that he discovers the joy of giving and sharing, as well as receiving: the joy of Christmas!

Why did Dickens choose the name “A Christmas Carol”? Well he wrote his story in five ‘staves’ instead of the normal ‘chapters’ implying that he wanted it to read like a piece of music, perhaps a carol, rather than just a story. There is also a mention of a lone, brave carol-singer attempting to sing a carol to Scrooge through his keyhole on the Christmas Eve in question, and being driven away by the wielding of a threatening ruler by Scrooge. The singing of carols was definitely a community-minded activity, precisely not something for Scrooge!

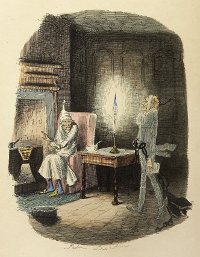

Illustration by John Leech (‘Punch’ magazine cartoonist) showing Jacob Marley’s ghost visiting Scrooge in Charles Dickens’ ‘A Christmas Carol’ (first edition, published by London-based Chapman & Hall in 1843).

The character Ebenezer Scrooge was very likely based on a real-life, eccentric gentleman, John Elwes, whose biography by Edward Topham published in 1790 instantly became a national bestseller. Dickens was a well-read man and would most certainly have read it. Elwes, born Meggot, assumed the name Elwes on being named heir to his bachelor uncle, Sir Hervey Elwes. He was never short of money as his father Robert Meggot was a wealthy brewer. Elwes was a patron of architects and was responsible for building half of Georgian London: the most part of St. James’s, Mayfair, Picadilly, Portland Place, Baker Street, Marylebone, and Oxford Circus. Despite being a millionaire, in later life he became a famous miser, dressing in rags and eating food full of maggots. He and the fictional Scrooge had other things in common, such as a jolly nephew and a skinny face with a pointed nose. However, there was one enormous difference: John Elwes inflicted his miserliness only on himself, always being kind, loving, and charming to others, and everybody adored him! A big difference, but still, the inspiration could have been there.

“A Christmas Carol” was not Charles Dickens greatest work. He completed it within six weeks just before Christmas 1843 to booster his faltering income from his novel “Martin Chuzzlewit”, which was being published in monthly installments. He was having big problems with his publisher, and he badly needed some ready cash as his wife was expecting their fifth child. On publication, which he ended up paying for himself, the book received a flood of criticism from powerful industrialists for being an indictment of industrial capitalism of the time. So why, despite not being his greatest masterpiece and its poor initial reception by “the people who mattered”, did “A Christmas Carol” go on to become probably his most popular book, and to even being credited with bringing back the merriment of Christmas?

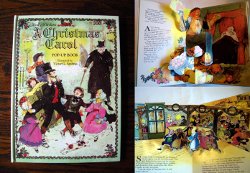

Well, Christmas comes but once a year (once too often, some cynics might say), while for those of us who love Christmas, this annual event, including the build-up to, it is something very special! Of course, it is the celebration of the gift of the baby Jesus, born simply in a stable to bring hope and to lighten and brighten our world, with all its bad news. It is also the time to enjoy being with our loved ones (if at all possible), giving, sharing, eating and drinking and hopefully relaxing together, no matter how much or little money we have to spend on it. Not to forget the annual ritual: the sending of Christmas cards, which helps us reconnect with old friends and family members who we don’t get to see too often – very nice that the multitude of charity cards now help us to remember the disadvantaged at the same time. So the fact that Christmas comes round faithfully every year gives this story a head start. Like the pop stars with their Christmas hits, if Dickens were still alive he would be able to cash in on the royalties of his story each year, with all those countless performances, not to mention the book, which has apparently never been out of print! A charming children’s pop-up version of the book, illustrated by Victor G. Ambrus and published by Methuen in 1986, is certainly out of print but good second-hand copies are still available from used-book sellers.

A fun, children’s pop-up version of “A Christmas Carol”, illustrated by Victor G. Ambrus (published by Methuen in 1986).

So what can account for the allure of Charles Dickens’ “A Christmas Carol”? Partly we may feel that we have to thank Dickens for re-energizing the festival which was once flagging and for giving us the nostalgic images of Christmastime in days gone by – but most especially, to my mind, the key is the opportunity given and taken to change for the better (it’s never too late) and the message of love and generosity which is embodied in the joy and wonder of Christmas.

How better to finish than with the original ending!

Scrooge was better than his word. He did it all, and infinitely more; and to Tiny Tim, who did NOT die, he was a second father. He became as good a friend, as good a master, and as good a man, as the good old city knew, or any other good old city, town, or borough, in the good old world. Some people laughed to see the alteration in him, but he let them laugh, and little heeded them; for he was wise enough to know that nothing ever happened on this globe, for good, at which some people did not have their fill of laughter in the outset; and knowing that such as these would be blind anyway, he thought it quite as well that they should wrinkle up their eyes in grins, as have the malady in less attractive forms. His own heart laughed: and that was quite enough for him.

He had no further intercourse with Spirits, but lived upon the Total Abstinence Principle, ever afterwards; and it was always said of him, that he knew how to keep Christmas well, if any man alive possessed the knowledge. May that be truly said of us, and all of us! And so, as Tiny Tim observed, God Bless Us, Every One!

THE END.

Great post, thought you might like my machinima version of A Christmas Carol http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=S9SBebs3A5I